Watch Out for Recuperation

Recuperation, in the sociological sense, is the process by which politically radical ideas and images are twisted, co-opted, absorbed, defused, incorporated, annexed and commodified within media culture and bourgeois society, and thus become interpreted through a neutralized, innocuous or more socially conventional perspective. More broadly, it may refer to the cultural appropriation of any subversive works or ideas by mainstream culture. — retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recuperation_(politics)

In 1940, Walter James (Lord Northbourne) wrote a book entitled Look to the Land — in it, he first used the term “organic” as applied to agriculture. He derived the term from the concept of “farm as an organism.” This was a rebuttal to the chemical farming techniques in use at the time. Lord Northbourne wanted farming to return to a more holistic practice — one in which soil health and plant/animal diversity was key.

Fast-forward 80 years to the present day. “Organic” foods can be found everywhere — in Walmart…. in Costco….. even brands such as Perdue Chicken have an “organic” line. Yes, these products are certified as “organic” because they have adhered to the various guidelines required. First, and foremost, this means the products should be clean of herbicides and pesticides — this is what most people think of as”organic.” Obviously, these products are better for us and the environment than conventionally farmed ones, but something of the original spirit and intent has been lost. In a nutshell, when we begin industrializing the production of these products, that beautiful idea of “farm as an organism” evaporates.

When evaluating agricultural procucts, I like to look at production quantities first — this is the whole point of industrialization — to increase quantity! An example: a single farmer produces eggs for sale at a farmer’s market. He has 40 chickens that run around eating bugs in the garden and leaving manure throughout. This is along the lines of a “farm as an organism” — it is a holistic being with all sorts of symbiotic relationships. The other side of the coin would be mass produced, industrialized “organic” eggs. Here you find thousands of birds locked in cages, fed the cheapest food possible (to keep overhead to a minimum), living in very unhealthy conditions…. you get the picture. This is not a holistic, “farm as an organism” setting.

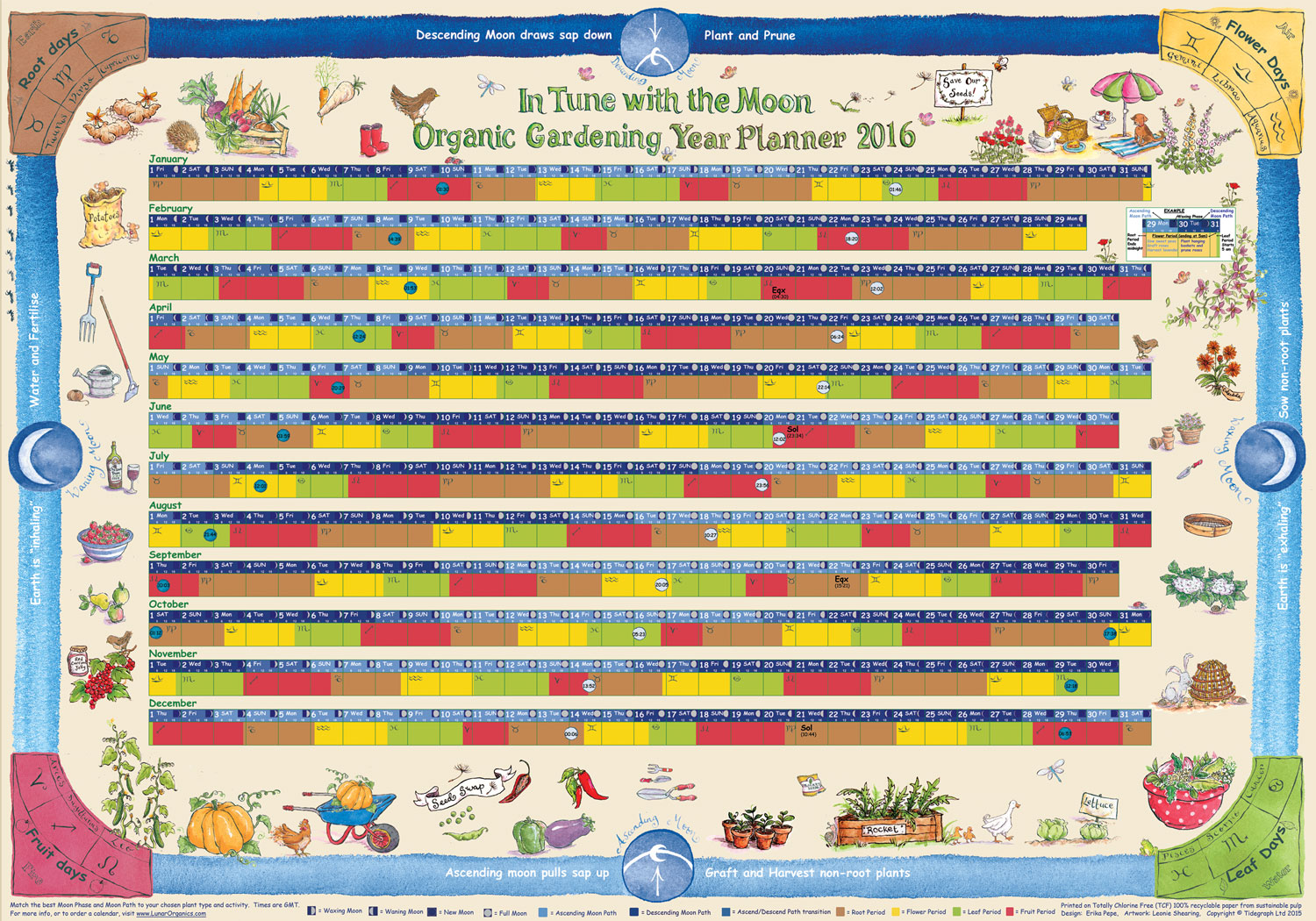

So, when is that threshold crossed? When do production numbers obliterate the original concept of “organic?” I can’t say. But I do know that the use of the term “organic” has been recuperated by big industry and know it means nothing. The same has been happening in the “biodynamic” world, where this term has been recuperated as well. Being “biodynamic” is so much more than merely utilizing the various preparations and using the calendar. Keep your eyes open and mark my word, we will see more and more “biodynamic” products popping up in the industrialized sector.

So…. what’s this have to do with wine? Wine is a difficult product to scrutinize. There is no ingredient label on a bottle of wine. Unless we are fortunate enough to visit where the wine is made, we really know very little about the farming practices. So, for me, I like to know quantities produced. “Biodynamic” is an intimate art, and if the farm is too large all that vital energy fades. Large farms are mono-crops, and mono-crops are the antitheses of holistic farming.

Don’t be fooled by labels. I guarantee you, there is a marketing meeting happening at E&J Gallo as we speak, and the guys in suits are talking about a “biodynamic” line. If you can’t meet your wine maker directly, at least know where the agenda of the importer/distributor lies.

Barefoot, Yellow Tail and Cupcake are sound wines.

The recent Bobby Stuckey polemic has got me thinking. Far more often than not, “natural” wine is critiqued on A) its flaws, and B) if its “story” is overshadowing the quality of the wine itself. Let’s break these 2 things down a bit…

Flawed vs. Sound

A flaw is pretty easy to grasp. If your wine tastes like vinegar, it is flawed — easy enough. The modern wine world is very accepting of cultured yeasts, mega-purple, and oak extracts — so, because modern wine-making textbooks train today’s wine-makers on the use of such techniques, we can say wines like Barefoot, Yellow Tail, and Cupcake are SOUND.

The Story Behind a Wine

Let’s get one thing straight — no matter how great the “story” behind a wine, we still have to enjoy drinking it! Here is where things get a tad confusing — as what, exactly, is a STORY of an agricultural/food product. Let’s invent a couple examples:

1) we have a skin-contact, orange wine, made from biodynamically farmed Aidani grapes, fermented spontaneously and aged in a qvevri, by a blind shaman in Minnesota. Only 50 cases exist. Great story! The taste: nail-polish remover and mousiness. “FLAWED.” UNSOUND.

2) A bottle of Barefoot Chardonnay. Grapes sourced from all over the place. No clear idea of how the wine is made or what exactly is in it. Tastes generic and consistently the same year after year. 8,331,238 cases produced. “UNFLAWED.” SOUND(?) (p.s. I hope to post later on some musings regarding the notion of being “sound” — and what, exactly, does it mean for a wine to be “sound”)

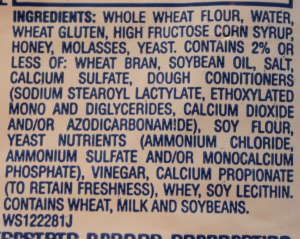

I find it funny, that while the story of wine #1 is so detailed, wine #2 really has no story. We COULD have a little more of a story if, by chance, a listing of ingredients were included on the label. But, alas, the wine industry falls outside regulations to which the rest of the food industry must adhere. In a strange way, the SOUND(?) wine — #2 — is better off WITHOUT a story. Sometimes it may be helpful , in this industry, to NOT TELL THE STORY!

It is interesting how wine falls outside the food realm, actually. Ask the general public if a loaf of Wonderbread is better then a baguette from the corner bakery. By far most people know Wonderbread is mass-produc ed crap — right-off the bat all you need to do is look at the list of ingredients. But wine doesn’t suffer the same scrutiny. Selling wine at a retail shop I see this everyday. I help customers who have just shopped for local, organic groceries, but who have no scrutiny when it comes to choosing a wine. Most would be horrified if they knew they were drinking “Wonderwine!”

ed crap — right-off the bat all you need to do is look at the list of ingredients. But wine doesn’t suffer the same scrutiny. Selling wine at a retail shop I see this everyday. I help customers who have just shopped for local, organic groceries, but who have no scrutiny when it comes to choosing a wine. Most would be horrified if they knew they were drinking “Wonderwine!”

The “story” of any food product begins in the farm — and that story continues to your glass or plate. I don’t want to turn my back on “stories” — in fact, I want a clear story every time I drink and eat!

I understand what Mr. Stuckey is saying. The criticism, though, should not be with “natural” wine — and the notion of being SOUND needs to go. The real test lies in a wine’s authenticity. When does a wine loose authenticity? There is a point when case production tips the scale from artisan to mass-produced — but when does that occur exactly? When has a wine had so many people involved in its production that authenticity is gone? This is for another posting… for now, start looking for the story in everything you consume, and realize that the lack of a story is more insidious than an overly detailed, colorful one.

Wine in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

…that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art. — Walter Benjamin

By now most people have heard of “natural wine.” The moniker “natural wine” has solicited (and continues to solicite) more debate then just about any other wine topic of today. “Raw wine,” “low-interventionist wine,” “naked wine”…… we continue to try to clarify what it is that defines these wines. Obviously, a brief search online will show there are various schools-of-thought regarding what designates a “natural wine” — VinNatur allows up to 50mg/l of SO2 in what they see as “natural” wines, while Les Vins S.A.I.N.S (Sans Aucun Intrant Ni Sulfite – “without any input or sulfur”) allows no additives whatsoever, yet tolerates gross filtration — all tangible specifications that can be verified. But how about we speak of wine in a not-so-objective manner? Much like that aura that Benjamin mentions above, I believe we can think about wine (and food, for that matter) with the same critique.

The aura is an effect of a work of art being uniquely present in time and space. It is connected to the idea of authenticity.

So how does wine express “authenticity”? How does it present itself uniquely in time and space? Better yet, how do we differentiate an “original” wine from a “reproduced” wine?

Let’s list a few tangible attributes of an authentic wine:

- Vineyards farmed organically and/or Biodynamically and hand harvested

- Indigenous yeasts — no cultured/laboratory yeasts

- Little to no use of SO2

- Unfined and no microbial filtration

- No use of additives such as pH adjusters, tannin, or colouring

- No enzymes

- No “heavy-manipulation” such as reverse osmosis, cryo-extraction, spinning cone, etc…

Easy enough to corroborate in a wine, right? But what about the intangible aspects — much like that aura that Benjamin speaks of in a work of art, there are attributes to a wine that can not be graphed or analyzed in a lab. The first things that come to mind (and the most often scoffed at) are the various biodynamic “rituals,” of sort, that can give wine immense vitality — a couple practices being the use of biodynamic “preparations” and the use of a biodynamic lunar calendar to determine when to harvest, bottle, and even drink.

In addition to the more codified biodynamic techniques, one can find a myriad of other personal rituals used in the making of these wines. The playing of music in both the vineyards and in the cellar is a fine example. I know of winemakers that believe their presence in the vineyard — the fact that they project love and care — is critical for a vital wine!

If you have a difficult time stomaching all this metaphysical hoodoo voodoo, think about home cooking. Does a Stouffer’s frozen meatloaf ever compare with your mother’s? Granted, quality of ingredients no doubt plays a role, but there is still the “made-with-love” factor (heard so often on cooking competition TV shows) that gives authentic food an aura.

As a coda I offer this short tale:

A fellow scientist once came to the home of Nobel Prize–winning physicist Niels Bohr and, having noticed a horseshoe hung above the entrance, asked incredulously if the professor believed horseshoes brought good luck. “No,” Bohr replied, “but I am told that they bring luck even to those who do not believe in them.”